Introduction

This post presents the article by Frassetto et al. entitled “JITGuard Hardening Just-in-time Compilers with SGX”. The authors present both an attack against JIT compilers (injecting malicious JIT intermediate representation) and a defense solution. We will focus on the defense part and look at the JITGuard design in details along with its security and performance analysis.

JITGuard Design

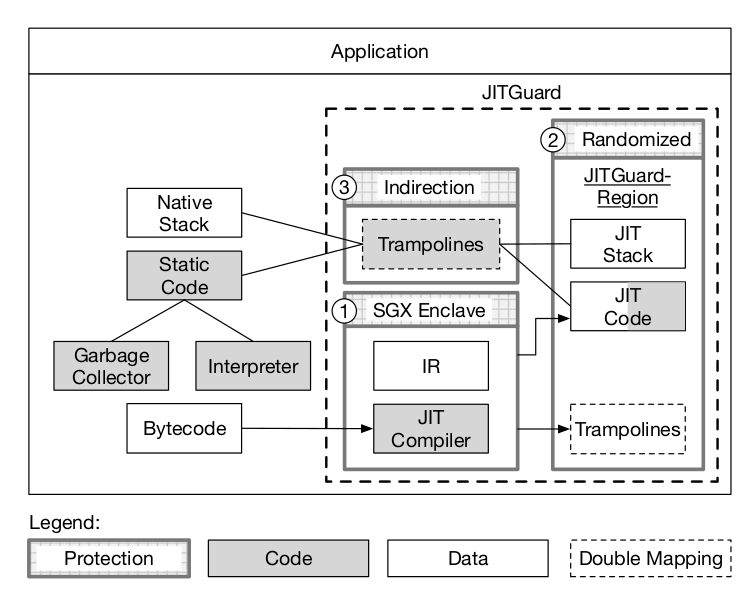

JITGuard presents a number of measures to isolate the JIT components from each other and attackers. The first thing to note from the design is that several elements are left outside of JITGuard: the garbage collector and interpreter, the static code (i.e. executed but not jitted) as well as the native stack and bytecodes.

JITGuard adds three mechanisms on the JIT compiler and critical components that interact with it, trampolines and the JIT IR.

- An Intel SGX enclave is used to isolate the JIT compiler and the intermediate representation it needs to recompile static code to machine code. This protects against memory-corruption vulnerabilities in the host process to launch attacks against the JIT compiler.

Note: The JIT code is not added to the enclave as the execution will be severely impacted by the amount of context switches needed at runtime to use it.

- Randomization of the JIT code and JIT stack memory addresses is used to protect against code-injection and code-reuse attacks as well as to prevent an adversary from injecting code.

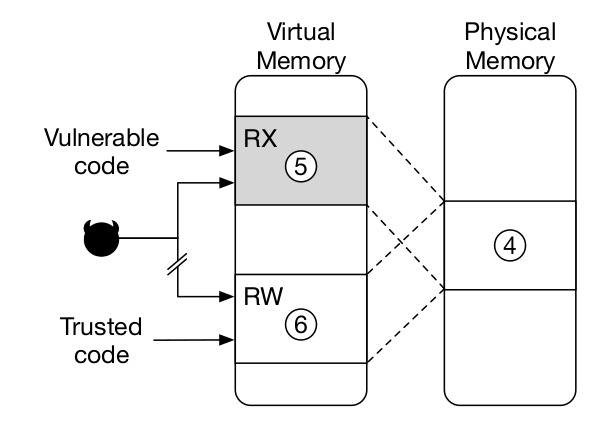

- An indirection through memory double mapping is used to protect trampolines. A segmentation register holds an offset to obtain the address of the JIT code. The content of this segmentation register is only available through a system call. This indirection layer needs to be both writable and executable to be updated by the JIT compiler. To do this in a secure manner, the same region in physical memory is mapped twice in the virtual address space of the process: the first is executable but not writable while the second is writable and not executable and randomized. The first one is used at runtime and called by the (potentially vulnerable) static code while the second is used by the JIT compiler to update the trampolines.

Isolation with SGX

The enclave contains the code and data of the JIT compiler and the randomization secrets. Switching to the enclave necessitates a context switch that is expensive and makes isolating the JIT code impractical. The JITGuard randomized region has its address hidden from the attacker and is emitted from the enclave, can be executed securely outside the enclave. It is necessary to avoid disclosing the location of the JITGuard-Region when using trampolines. Several points need particular attention:

-

Initialization: The initialization phase is launched from the static code part of the application. The initialization component allocates two memory regions: the trampoline and JITGuard-Region. All memory accesses to the JITGuard-Region are mediated through the enclave to prevent the address from being written to memory which is accessible to the attacker. This region holds the JIT code, the JIT stack and the writtable mapping of the trampolines. The second region holds the executable mapping of the trampolines. Finally, JITGuard sets up the JIT compiler enclave providing the address of the JITGuard-Region as a parameter.

-

Runtime: (1) Compatibility, a dedicated system call wrapper stores the required parameters in the designated registers inside the enclave to issue the

syscallinstruction without modifying the application memory. (2) Leakage-resilience, to avoid manual review of the source code to check no instruction leaks the JITGuard-Region address, JITGuard converts the real pointer to the JITGuard-Region into a fake pointer by adding a random offset (stored in the enclave) during the creation of the enclave. All functions that require access to the JITGuard-Region (e.g. to emit JIT code or modigy the trampolines) to first convert the fake pointer back to the original pointer. At the same time, JITGuard verifies that the code does not leak the pointer to memory outside of the enclave. (3) JIT Code Generation, to trigger a JIT compilation, the interpreter has to initiate a context switch to the enclave. -

SpiderMonkey: The baseline JIT compiler code is speculatively optimized by another compiler called IonMonkey. It was disabled when implementing JITGuard but should follow the same guidelines to be included. Note that SpiderMonkey enforces W⊕X that simplifies the instrumentation of the code as only a small portion of the compiler functions modify the JIT code.

Control-flow Transfer

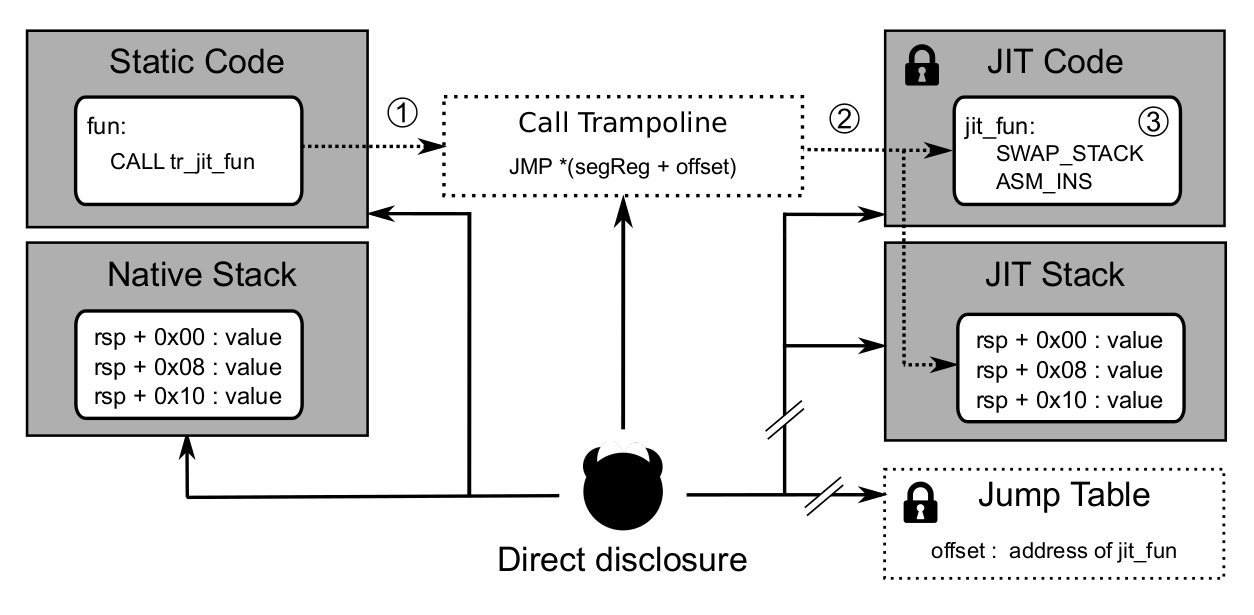

Since the static code and JIT code interfere up to 600 times per millisecond and that the attacker has access to the host memory, it is needed that no pointer from the randomized region leaks into the non-randomized part of the host memory. Both code regions often use the same stack during execution. A JIT stack is needed and hidden in the randomized region. This way, the randomized stack can be used safely during JIT execution and an adversary cannot recover a return pointer to the JIT code from the native stack. The two scenarios are the following:

(I) Static code calls JIT code: Static code calls JIT code functions when switching from interpreted to machine code JIT functions. (1) Static code calls a trampoline to initiate the switch, each trampoline targets a single JIT code function. An x86 segment is setup at initialization time to hold a random address. (2) This way, jumps only need to write an offset to that segment to the trampoline. The start address of the segment cannot be disclosed by the attacker. The jump table is protected as well because it is located inside a randomized region.

Note: The base address of the segment can only be disclosed using a system call,

arch_prctlor using a special instruction,rdgsbase. The instruction has to be explicitely activated by the operating system which is not supported in Linux. It is used in the initialization phase of JITGuard and there only.

(3) The JIT code switches from the native stack to the randomized stack. In particular, the randomization code updates rsp and rbp to their new location inside the randomized area and saves their previous values in the JIT stack. Alignment is checked and updated if needed. When the JIT function returns, the randomization code restores the previous values and returns execution.

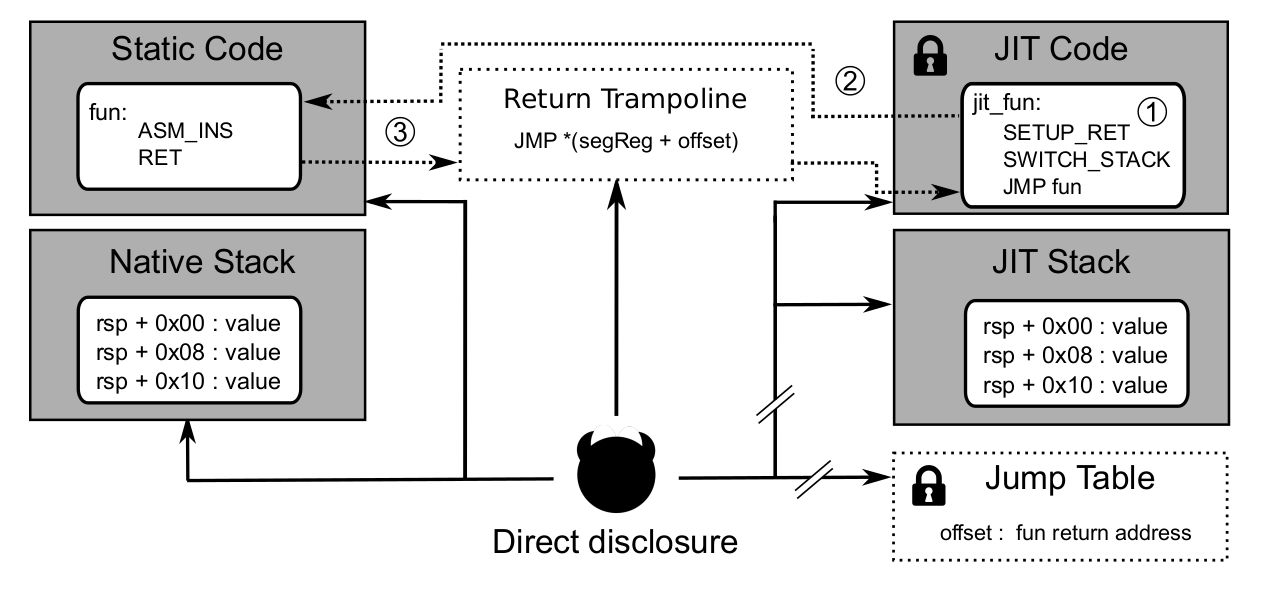

(II) JIT code calls static code: JIT code needs to call functions that are not in machine code (e.g. a library function implemented in static code). Usually, the return address is stored on the stack and if the JIT code calls the native code without special measures, the native code can easily retrieve the return pointer from the stack and disclose the JITGuard-Region. Return trampolines are put on the stack which then retrieves the original return address using the randomized segment.

(1) The JIT code has to prepare the return trampoline prior to calling the static code function. It will store the return address to the JIT code in a jump table located in the randomized segment, then switch the stack pointer back to the native stack, save the offset between the two stacks in the randomized segment then set the return address on the native stack to point to the return trampoline. (2) Next, the static code function executes until it returns. (3) The return trampoline retrieves the original return address using the segment register and an offset in the jump table. It then returns to the JIT code.

Security Analysis

The goal of JITGuard is to mitigate code-injection, code-reuse and data-only attacks against the JIT code.

Code injection/reuse attacks: Both code injection and reuse techniques are used by the attacker to execute arbitrary code after the control flow has been hijacked. However, this requires the attacker to know the exact address of the injected code or gadget. JITGuard does not prevent the attacker from injecting code using techniques like JIT spraying. However, the attacker cannot disclose the JITGuard-Region which contains the JIT code and data. Therefore, the attacker cannot hijack any code pointers used by the JIT code and cannot exploit the generated code for code-injection or code-reuse attacks.

Information disclosure attacks: The security of JITGuard is built on the assumption that the attacker cannot leak the address of the JITGuard-Region. Seven components interact with the randomized region and hence could leak the randomization secret:

-

Initialization code: The JITGuard-Region is allocated through the

mmapsystem call and the resulting address is then passed to the enclave. All registers, local variables and the stack memory are set to zero. This ensures the address is not stored in the memory outside of the enclave. -

JIT compiler in the enclave: The first action of the initialization function is to obfuscate the address of the JITGuard-Region. The JIT compiler will only work on the fake pointers. They are useless to an attacker without the random offset, which is stored securely inside the enclave. 11 functions were patched to use the fake pointers.

-

JIT code: The JIT code does not leak any pointers to the JITGuard-Region to attacker-accessible memory. This would need to leak the program counter or stack pointer to the heap which is not the case in the JIT compiler.

-

Trampolines: Trampolines adjust the stack pointer to point to the native or JIT stack and they use a segment register as an indirection to access the JITGuard-Region. The segment base is set in the kernel and is transparent to user mode.

-

JIT/static code transitions: Any arguments and CPU registers are checked to make sure they do not represent or contain pointers to the JITGuard-Region. Similar check verify the return value of JIT-compiled functions to static functions.

-

Garbage collector: The code responsible for garbage collection of JIT code is moved inside the enclave and an attacker cannot leak addresses to the JITGuard-Region by disclosing memory used by the garbage collector.

-

System components: Linux’s

procfile system provides a special file for each process that contains information about its complete memory layout. If the attacker gains access to this file, they can disclose the address of randomized memory sections. However, this file is mainly used for debugging purposes and requires higher privileges by default.

Data-only attacks: IR is mitigated because put into the enclave alongside the JIT compiler. JITGuard also protects against attacks that aim at the temporary output buffer of the JIT compiler because this buffer is inside the enclave. The only attack vector remaining is the direct input, i.e. source code or bytecodes. The bytecodes are designed in a way that potentially harmful instructions cannot be encoded. For instance, it does not support system call instructions, absolute addressing, unaligned jumps or direct stack manipulation. As a consequence, an adversary cannot utilize the bytecode to force the JIT compiler to create malicious native code.

Performance Analysis

JITGuard was evaluated using the JavaScript benchmark Sunspider 1.0.2. It includes tasks such as JSON demangling, code decompression or 3D raytracing. The dynamic frequency scaling of the processor has been disabled. The overhead of each component was measured independently:

Static code > JIT code randomization: The randomization of the stack during the transition from static code to JIT code has no measurable overhead since only a small constant overhead is added to each call to the JIT code (max 1.6%).

Static code > JIT trampolines: The trampolines that are used for calls from the static code to the JIT code add an average overhead of around 1.0%, since only one jump instruction is added. However, a higher than average usage of trampolines can make this overhead grow up to 10% to 19%.

Both trampolines and randomization: The average overhead in this case is around 10% and is mostly due to the imbalance between cal and ret instructions, which trashes the processor’s return stack. This is necessary to implement the security guarantees.

Full JITGuard: The average overhead for the complete scheme is 9.8%, which is still an order of magnitude over the interpreted code.