Introduction

This post presents the article by Park et al. entitled “NoJITsu: Locking Down JavaScript Engines”. The authors present both an attack against JIT compilers (injecting malicious bytecodes) and a defense solution. We will focus on the defense part and look at the NoJITsu design in details along with its security and performance analysis.

NoJITsu Big Picture

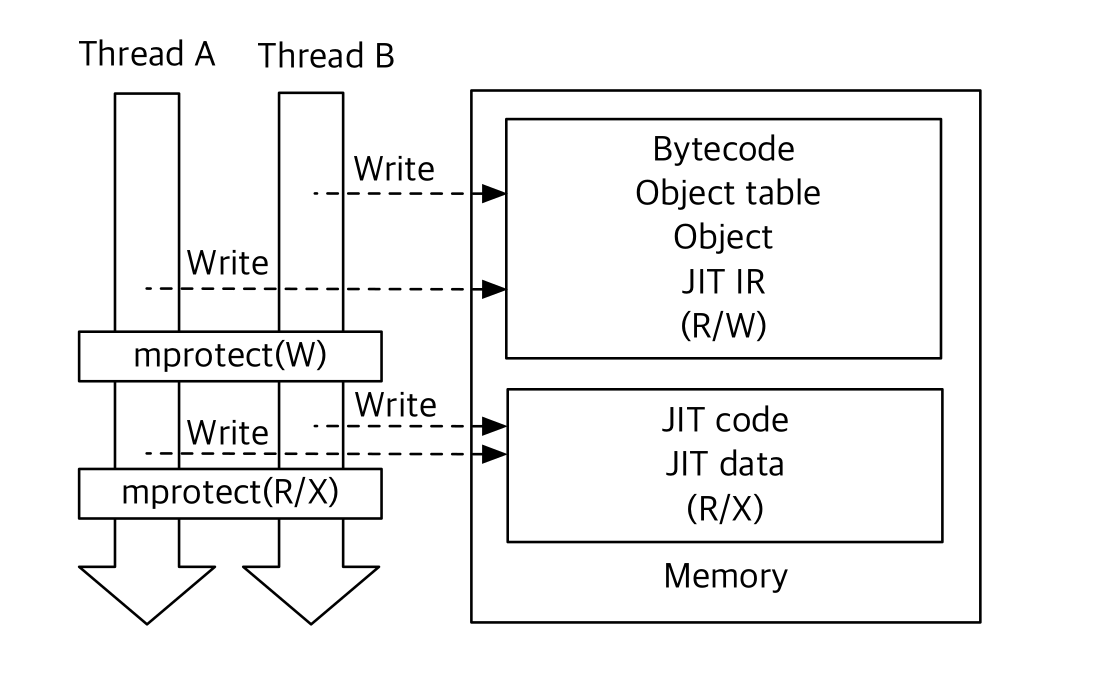

NoJITsu goal is to deploy fine-grained security policies around critical objects that are used at runtime by the VM. The overview of the changes between the legacy version and NoJITsu is:

- Legacy: Runtime engines do not distinguish between different kinds of data sections and have naive or no explicit security policies for them within the application’s address space. In the legacy design (on the left) several critical components are stored in

Read/Writememory. For example, bytecodes, object tables and the JavaScript objects are in writable memory regions for their entire lifetime even though it is rarely overwritten.

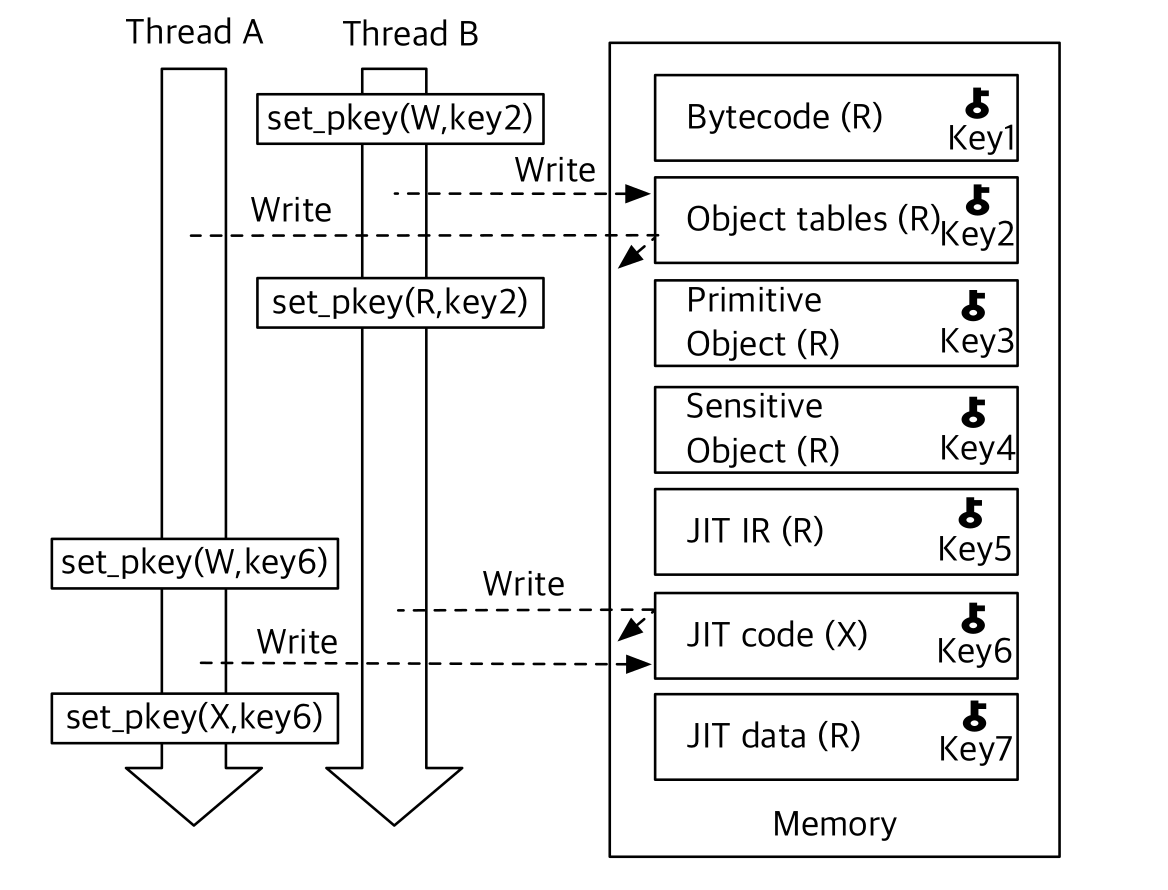

- NoJITsu: NoJITsu deploys fine-grained memory policies to lock down access permissions for each of the main data regions identified on their lifetime and usage within the JIT engine. Bytecode, object tables and JavaScript objects are stored in read-only memory and write access to the regions are only granted when it is needed. JIT code regions are marked as execute-only.

Every data structure is allocated with the correct memory permissions and its corresponding key. Data structures are separated upon allocation so that no memory page contains structures from multiple domains. Next, the permissions of each function are deducted from the engine needs based on the types of data it may access. Places where a temporary relaxation of the permissions (to change an object or write machine code) are identified through a dynamic analysis and instrumented with a piece of code to set and reset memory permissions. Restricting memory accesses rely on a hardware-based measure (Intel’s MPK) to change memory permissions without modifying page table entries or flushing the TLB.

Components Isolation

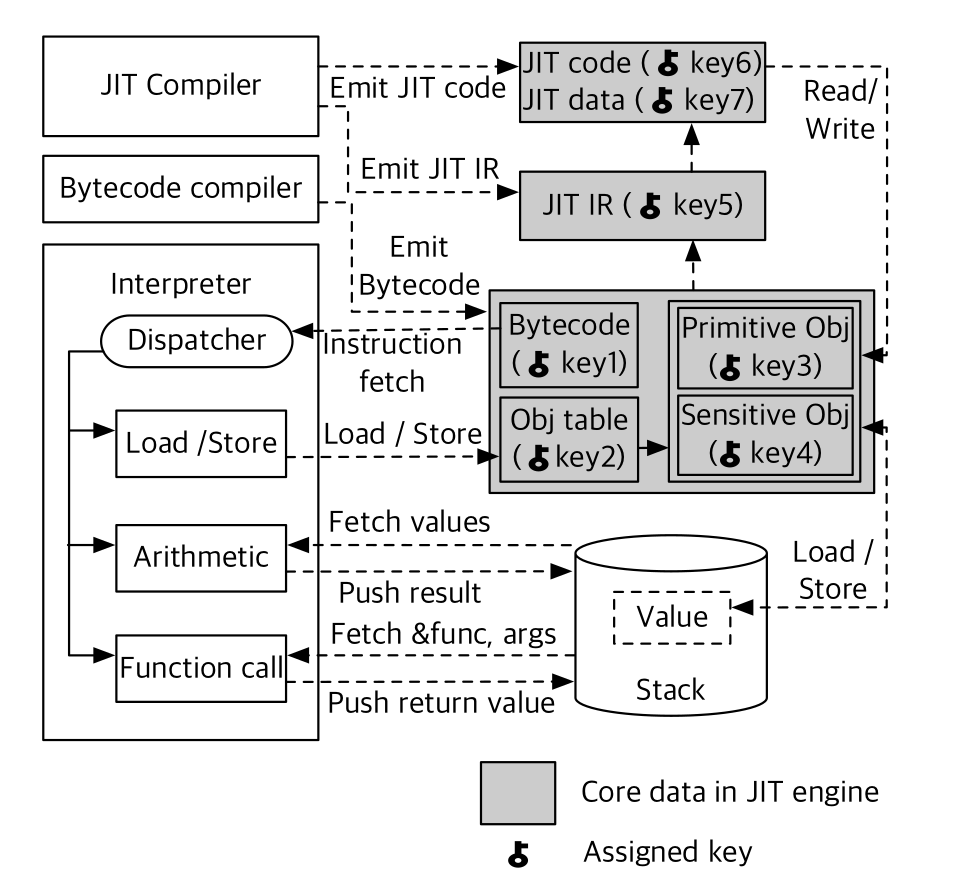

All components have their own isolation needs and properties:

JIT code: The JIT code cache contains dynamically generated machine code instructions. To defend against injection attack, it should be kept non-writable except at generation. It also needs to be non-readable to avoid JIT-ROP attacks which clashes against the fact that the JIT code cache may contain readable data such as constant values which are too wide to be embedded into instructions. A clean separation is needed to define a read-only data zone and execute-only code zone.

Static code: The static code consists of the code of the engine itself and the code of libraries loaded in memory. The attacker cannot inject malicious code into this region but it consists of an abundance of code-reuse gadgets. This region should then be set as execute-only.

JIT IR: This intermediate representation is used during the compilation of bytecode to machine code. Even with its short lifetime, it can be corrupted to compile malicious machine code. The JIT IR code is protected to be read-only and set as write-only only for the thread that compiles the code.

Bytecode and object tables: Bytecode and object tables are set as writable only when they are generated during compilation then switched to read-only. A write access is allowed only when the script parser generates them and immediately makes them non-writable again after.

JavaScript objects: Unlike bytecode and object tables which must be written only once, data objects can be frequently reused and updated during the program execution. Several attributes are updated very often such as the reference counter for the garbage collector. A dynamic analysis technique is used to identify permitted write operations for each object.

The objects are split into two protection domains depending on the types they encapsulate: one for sensitive data objects (i.e. objects that manipulate sensitive information such as function pointers, object shape metadata, scope metadata or JIT code) and another for primitive data objects (i.e. integers, characters or arrays). Corrupting a sensitive object allows the attacker to seize control over the engine while corrupting a primitive object is not enough but may help corrupt a sensitive object. Doing this separation can ensure both these domains cannot be writable at the same time, this way an attacker cannot use an object type confusion vulnerability. One issue is that JIT code execution might manipulate objects too and changing permissions may introduce substantial run-time overheads. All access restrictions to primitive data objects are lifted while JIT code executes. However protection for sensitive data objects stay up even during JIT execution.

Implementation

Hardware mechanism: The domain-based access is built on top of Intel Memory Protection Keys (MPK). It allows user-space programs to manage access permissions for up to 16 memory domains. To change permissions, the program uses an unprivileged instruction to write to the thread-local PKRU register. However, MPK does not make it possible to define execute-only memory regions, so the JIT code and statically generated code are allocated on executable pages then MPK revokes the read and write privileges.

A signal handler is added to check if the an access fault is caused by MPK and correct permissions accordingly. Accessors are the main users of permission change as they touch protected object and need to access either regular attributes or metadata (i.e. GC).

All accesses to objects that triggered the signal are patched and extended continuously to cover the different cases.